Actionable improvement – ‘10 things every teacher educator should know’

How can teacher educators ensure their trainees have concrete steps to take in order to develop knowledge or hone a specific skill? In the eighth part of our ‘10 things every teacher educator should know’ series we explore the techniques and methods we use to help structure this crucial part of the development cycle.

Feedback is integral when training to teach, because novices need advice from more knowledgeable and skilful teachers if they’re to improve. But if we think about how often feedback is misinterpreted or simply not followed in teaching, it would be easy to become disheartened.

Teachers are very busy and can often be cognitively-overloaded – in other words, if they receive too much feedback it can be confusing or unhelpful.

And this is why the most complex part of the developmental cycle (outlined in the previous article of this blog series) is arguably the implementation stage: what will the trainee actually do in order to improve? To help with this, our teacher educators use a more specific framework to give their trainees concrete steps to develop their knowledge or hone a specific skill.

For this, we use an adapted version of the Bambrick-Santoyo feedback protocol, particularly after lesson observations. There are five steps (five Ps) to guide our discussions:

- Praise strengths

- Probe development areas

- Set Precise actions

- Plan ahead

- Practise based on the plan

Defining precise actions and planning for their completion makes it much more likely that trainees will complete them (for example: ‘Plan the questions you’ll ask after the starter activity in your Year 9 lesson on Tuesday’ rather than ‘Plan some questions before your lessons’). Practising with an expert as part of this cycle enhances progress further.

This complements Rosenshine’s principle of combining a small amount of feedback with a chance to practise it afterwards, to give time for the feedback to be actioned. This should happen before giving any additional feedback.

So how else do we approach giving our trainees effective feedback? Here are our top three approaches:

1. It’s important to get the scope of the feedback right. If it’s too wide in scope it won’t be actionable, but if it’s too granular it might not be applicable to other practice. A good principle is that the feedback should last about two weeks, to give enough time for the trainee to put it into practice and reflect on it.

2. It’s also crucial to set the parameters of the feedback. Teaching is a complex creature, and as the trainee becomes more skilled it becomes even more so. It’s therefore important to be clear on what the primary focus is (even if this feels a little artificial).

3. Finally, teacher educators need to carefully consider the root cause of the area for development. For example, when thinking about inconsistency in behaviour management, is the root cause that the trainee needs to raise their expectations of all learners’ behaviour (TS1)? Or is it because they aren’t noticing the behaviour in the first place (TS7)? Or another reason entirely?

Case study: the difficulty in identifying root causes and how to overcome it

Peps Mccrea talks of “pupil, path and pedagogy” as making the difference between a novice and an expert teacher, and we think the same principle applies to teacher educators.

An expert teacher educator is able to apply their knowledge and understanding of their pupil (in this case their mentee), the path they’re on (in this case the training their mentee has received and will go on to receive), and pedagogy (in this case the mentor’s knowledge of what the most transformational next step would be). So for teacher educators to become experts, they need to have an expert grasp of trainee, training, and transformational next step.

Scenario

A trainee showed excellent practice in an observed lesson, but their practice was inconsistent. The mentor had observed that the trainee had good subject knowledge, was able to explain concepts effectively and was able to enact the behaviour policy successfully. The issues were that the activities being set for pupils often didn’t lead to pupil progress.

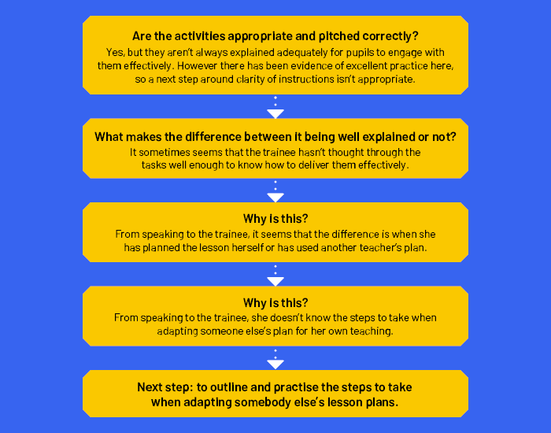

How the mentor identified the root cause

Conclusion

It’s clear that this mentor had excellent understanding of the trainee, their training, and a transformational next step. He knew the trainee’s strengths from previous observations and conversations. From knowing her character, he knew the issue wasn’t down to something like poor time management. He also knew that from her training she had lots of experience and practice of planning activities for progress, giving instructions, behaviour for learning strategies, and transitions, so it was less likely to be these areas. And using his experience he was able to identify a transformational next step – knowing that this wasn’t something that had been explicitly covered before, that the trainee would continue to use shared plans (and that was a net benefit at this stage), and that this was the main contributor to inconsistent practice.

Once the root cause was established, and the appropriate development point identified, it was then possible to set very small, concrete actions against this. This is a little like setting the learning objective versus the lesson outcomes for a lesson: the overall area for development is set first, which should be mapped against a set of success criteria (what does ‘good’ in this area look like?), and then the concrete actions for the trainee are set against this.

In summary, drilling down into the concrete steps trainees need to take in order to improve their teaching and being really specific about how they will implement the feedback they are given is the first building block in helping them to close the ‘knowing-doing gap’ identified by Christodoulou.

About the author

Jenna is a teacher educator working for Teach First in the South West. Find her on Twitter @JAnderson1985.

About this series

We train thousands of new teachers each year, but this is only around 5% of all new teachers. So we wanted to share some of the thinking behind our teacher education in this series of blogs. We hope these blogs will be helpful for the thousands of schools that support new trainee teachers each year, and act as a starting point for conversations with other teacher educators – so we can all keep learning and improving.

This is our current thinking but we’re always reviewing and learning from research, other organisations and practice. We want your views and feedback: What do you agree with? Is there anything you disagree with? What have we missed? Let us know on twitter – you can chat to our teacher education leads @FayeCraster and @Reuben_Moore (and we’re on @TeachFirst)